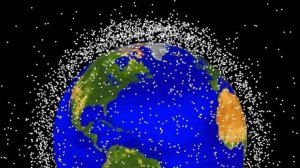

Right now, there are more than 300,000 pieces of debris larger than a centimeter in diameter orbiting Earth. Most are shrapnel from discarded rocket stages that have exploded after use, or satellites that have collided. Colloquially, all this debris is usually called “space junk.”

Together, the Department of Defense and NASA track the orbits of the 19,000 or so pieces of junk that are larger than a softball, alerting satellite operators when any satellite — including the International Space Station — is in danger, so they can move it.

But doing so takes time and resources. What’s more, the cloud of debris has been steadily growing over time, and some scientists worry that if we’re not careful, we could trigger a chain reaction: More space junk raises the chance of collisions, which in turn can lead to even more debris, until the sheer volume of space junk makes parts of space unusable.

“Space is a finite resource — just like the atmosphere, and the water, and the Earth,” says William Schonberg, an aerospace engineer who designs spacecraft to minimize damage from orbital debris. “We need to be careful about how we use it.”

Why space junk is a problem

E ven small pieces of debris in orbit around Earth can cause a surprising amount of damage because of a basic reason: speed.

ven small pieces of debris in orbit around Earth can cause a surprising amount of damage because of a basic reason: speed.

“All the objects in Earth’s orbit naturally have a high velocity,” says Holger Krag, head of the European Space Agency’s Space Debris Office. (If they weren’t traveling that fast, they’d simply drop to Earth.)In low Earth orbit, this speed is around 16,000 miles per hour. “Even a centimeter-long screw can generate the energy of an exploding hand grenade.”

As a result, collisions have to be avoided at all costs. Using ground-based radar and other instruments, the Department of Defense and NASA keep track of about 19,000 pieces of debris larger than five centimeters — the ones big enough to cause significant damage.

“We do an assessment for every operational satellite, looking typically three days into the future, and if we think that some other object is going to come close to hitting it, we notify the owner-operator,” Nicholas L. Johnson, then-chief scientist at NASA’s Orbital Debris Program, told me in 2012. About once a week or so, satellites are moved to prevent a collision.

Because there’s crew on board, the International Space Station is treated with extreme delicacy and is moved if there’s more than a 1 in 100,000 chance something will collide with it. In a few cases, warning hasn’t come in time, and astronauts have had to quickly take shelter in the capsules that serve as the station’s lifeboats.

Even with these preventative measures, though, debris are a long-term issue for space operations as a whole. One problem is that a steady stream of even tinier, sand grain-sized particles can gradually the surface of all spacecraft in orbit.

And there’s a bigger concern for heavily-trafficked orbits — such as low Earth orbit and geosynchronous orbits (often used for communication satellites, so they can stay fixed over one location on Earth). As these orbits fill with debris, they become more and more expensive to use. “Every collision avoidance maneuver means loss of mission time,” Krag says. “And you have to use manpower and fuel to carry them out.”

All debris eventually falls back to Earth given enough time — and objects in lower orbits fall much faster, over the course of a few years, because traces of atmosphere drag on them and slow them down. But those in higher orbits might take decades or even centuries. And if we’re not careful, some orbits could become so clogged with junk that they’re impossible to use.

Where all the space junk came from

A few different factors have contributed to the steady accumulation of orbital debris ever since we started using space in the 1950s.

One is the fact that for decades, the rockets we used to lift spacecraft into orbit were only designed with the first few minutes of flight in mind. “We didn’t think at all about how the object might behave after years or decades,” Krag says.

As a result, rocket components were commonly left in orbit with tiny amounts of extra fuel and built-up pressure inside. When an object in orbit leaves the shadow of the Earth and is hit by sunlight, its temperature can swing by hundreds of degrees. This has led many rocket stages to explode, sending thousands of shards of metal cascading in orbit.

In the 80s, scientists recognized the problem, and now, rockets are designed so that they can be fully emptied after use. These intact rockets, along with deactivated satellites, make up a minority of the pieces of debris in orbit.

But two recent events generated another 5,000 pieces of tracked debris, generating about a quarter of the total.

In 2007, China intentionally destroyed one of its weather satellites in orbit as part of a military test, generating about 3,000 pieces of debris. Even worse, it was done in a higher orbit than other anti-satellite tests previously conducted by the US and Russia, so the debris will take much longer to come down. Other countries criticized the test, but the damage was done.

Then, in 2009, two satellites — a deactivated Russian military satellite and an active US communications satellite — accidentally collided, creating a shower of another 2,000 or so pieces of debris.

What’s going to happen to space junk in the future

The 2009 event was especially alarming because it may be a sign of things to come: if space gets too crowded with debris, it could trigger a positive feedback loop, in which collisions beget debris, which beget collisions.

Some scientists, in fact, believe this scenario (called the Kessler syndrome) is already happening, just slowly. Unlike in the movie Gravity, the chain reaction would accelerate slowly, over the course of decades: right now it’s estimated that one collision will occur every five years, and if things get worse, the rate could increase to one collision annually within 50 to 100 years.

Still, there’s disagreement over whether this is happening yet — and spacefaring nations are generally being more careful nowadays. Rockets are drained of fuel and pressure after use, and satellite operators are now required to move their satellites down to a lower altitude after use, so they’ll fall back to Earth more quickly, or take them up to an unused “graveyard” orbit.

Still, there’s tons of debris already in orbit. If we did enter a scenario in which debris accumulated uncontrollably, people have drawn up some ideas for cleaning up our orbits: crafts that would use nets or harpoons to grab derelict satellites to bring them down, for instance, or a spacecraft that would grab debris, throw it down to Earth, and use the resulting momentum to move on to the next object.

At the moment, though, these ideas are purely hypothetical, and all of them would be extremely expensive. If we want to continue relying on Earth’s orbit for communication, navigating, and all other sorts of useful technologies, we need to be more careful with it going forward.